Command-line versus GUI program

TL;DR

When you are exploring a problem, in general first write a command-line program whenever possible.

It will take less effort to write then a full-blown GUI.

Introduction

Recently I wrote a program to remove the protection from ms-excel files.

The original version was written as a command-line program. Later I re-used the relevant code for a GUI program for use on ms-windows. This was mainly for the benefit of some colleagues who are not comfortable with using the command-line.

In this article I want to contrast the two programs.

Both programs can be found in my public scripts repository.

The command-line version is called unlock-excel.py, while the GUI version

is unlock-excel.pyw.

Excel 2007+ files are essentially zip-files filled with mostly XML files.

Since Python has a module for opening zip-files, and we can use regular

expressions to remove the offending sheetProtect and workbookProtect

tags, it is well-suited to this task.

Command-line program

The command-line version is around 50 lines of code, 10 additional blank lines and 8 lines of comments.

The main function is pretty simple.

def main(argv):

logging.basicConfig(level='INFO', format='%(levelname)s: %(message)s')

if not argv:

logging.info(f'unlock-excel.py v{__version__}; no files to unlock')

print('Usage: unlock-excel.py <file> <file> ...')

sys.exit(0)

for path in argv:

try:

backup_path = backup_file(path)

remove_excel_password(backup_path, path)

except (ValueError, shutil.SameFileError) as e:

logging.info(e)

For each of the file names given on the command-line, it calls two functions.

The first function backup_file tries to create a backup file by appending

-orig to the filename and make a copy.

def backup_file(path):

first, last = path.rsplit('.', maxsplit=1)

backup = first + '-orig' + '.' + last

logging.info(f'moving "{path}" to "{backup}"')

shutil.move(path, backup)

return backup

The second function remove_excel_password does the actual modification of

the xls[xm] files by opening it with the zipfile module and writing the

members (modified if necessary) to a new zipfile.

def remove_excel_password(origpath, path):

if not zipfile.is_zipfile(origpath):

raise ValueError(f'"{origpath}" is not a valid zip-file.')

with zipfile.ZipFile(origpath, mode="r") as inzf, zipfile.ZipFile(

path, mode="w", compression=zipfile.ZIP_DEFLATED, compresslevel=1

) as outzf:

infos = [name for name in inzf.infolist()]

for info in infos:

logging.debug(f'working on "{info.filename}"')

data = inzf.read(info)

if b'sheetProtect' in data:

regex = r'<sheetProtect.*?/>'

logging.info(f'worksheet "{info.filename}" is protected')

elif b'workbookProtect' in data:

regex = r'<workbookProtect.*?/>'

logging.into('the workbook is protected')

else:

outzf.writestr(info, data)

continue

text = data.decode('utf-8')

newtext = re.sub(regex, '', text)

if len(newtext) != len(text):

outzf.writestr(info, newtext)

logging.info(f'removed password from "{info.filename}"')

Note that I tend to use the logging module for status updates.

There is a tradition from UNIX that command-line programs should be silent unless

errors occur.

This tradition made sense in the days of teletypes since paper costs money.

On a terminal emulator, not so much.

That is not to say that a program should be gratuitously verbose.

But in this case I’d like to know how many sheets had a password set and if it

was successfully removed.

Binary files like ms-excel files are pretty opaque otherwise.

GUI program

By contrast, the GUI version has approximately 190 lines of code, 43 lines of comments and 33 blank lines.

A GUI program is basically a combination of state data and a lot of functions that are called from the GUI’s event loop. Your program is basically a bolt-on to the GUI toolkit.

In this case I’m using the tkinter toolkit that comes with Python.

Some of the functions are called in reaction to the user manipulating a control (e.g. pressing a button). These are generally described as “callbacks”. Others are set to run whenever there are no events to process. A general name for those is an “idle task” or “timeout”.

Such idle tasks shouldn’t take too long. Anything up to say 50 ms is fine, since a user is unlikely to notice such a small amount of time. Functions that run longer would noticeably make the GUI unresponsive since they interrupt the event loop.

For longer running tasks, there are basically three possibilities;

- Break them up into smaller tasks that are executed sequentially.

- Run them in a separate process

- Run them in a separate thread.

The python.org implementation of Python (“CPython”) has the restriction

that only one thread at a time can be executing Python bytecode.

So a computation thread would still interfere with the event loop running in

the main thread, but on a lower level.

Additionally, not all GUI toolkits are thread-safe, so you should only make

GUI calls from the main thread unless you know otherwise. Although it seems

that with Python 3.x, tkinter is thread-safe.

The combination of these facts makes multithreading tricky for Python GUI

applications in my opinion. It’s fine if the not-main threads are doing I/O or

if they use e.g. time.sleep(). But doing long calculations might still

make the GUI less responsive.

In this case, I will be using the first option since it is relatively easy to split up the processing of an ms-excel file into small steps:

- Open the source and destination files.

- Make a list of the internal files.

- Read an internal file, filter it if necessary and write it to the destination file. This step is repeated as often as necessary to process all internal files.

- Close the source and destination files.

When starting the program, two user-provided function will be called first.

The first function creates the widgets in the root window.

def create_widgets(root, w):

"""Create the window and its widgets.

Arguments:

root: the root window.

w: SimpleNamespace to store widgets.

"""

# Set the font.

default_font = nametofont("TkDefaultFont")

default_font.configure(size=12)

root.option_add("*Font", default_font)

# General commands and bindings

root.bind_all('q', do_exit)

root.wm_title('Unlock excel files v' + __version__)

root.columnconfigure(3, weight=1)

root.rowconfigure(5, weight=1)

# First row

ttk.Label(root, text='(1)').grid(row=0, column=0, sticky='ew')

w.fb = ttk.Button(root, text="Select file", command=do_file)

w.fb.grid(row=0, column=1, columnspan=2, sticky="w")

w.fn = ttk.Label(root)

w.fn.grid(row=0, column=3, columnspan=2, sticky="ew")

# Second row

ttk.Label(root, text='(2)').grid(row=1, column=0, sticky='ew')

w.backup = tk.IntVar()

w.backup.set(0)

ttk.Checkbutton(root, text='backup', variable=w.backup,

command=on_backup).grid(row=1, column=1, sticky='ew')

w.suffixlabel = ttk.Label(root, text='suffix:', state=tk.DISABLED)

w.suffixlabel.grid(row=1, column=2, sticky='ew')

w.suffix = tk.StringVar()

w.suffix.set('-orig')

se = ttk.Entry(root, justify='left', textvariable=w.suffix, state=tk.DISABLED)

se.grid(row=1, column=3, columnspan=1, sticky='w')

w.suffixentry = se

# Third row

ttk.Label(root, text='(3)').grid(row=2, column=0, sticky='ew')

w.gobtn = ttk.Button(root, text="Go!", command=do_start, state=tk.DISABLED)

w.gobtn.grid(row=2, column=1, sticky='ew')

# Fourth row

ttk.Label(root, text='(4)').grid(row=3, column=0, sticky='ew')

ttk.Label(root, text='Progress:').grid(row=3, column=1, sticky='w')

# Fifth row

sb = tk.Scrollbar(root, orient="vertical")

w.status = tk.Listbox(root, width=60, yscrollcommand=sb.set)

w.status.grid(row=4, rowspan=5, column=1, columnspan=3, sticky="nsew")

sb.grid(row=4, rowspan=5, column=5, sticky="ns")

sb.config(command=w.status.yview)

# Ninth row

ttk.Button(root, text="Quit", command=do_exit).grid(row=9, column=1, sticky='ew')

The widgets that have to be accesse of widgets that have to be accessed later

later are stored in a types.SimpleNamespace.

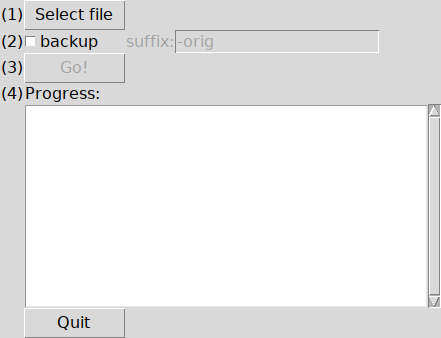

The window it creates looks like this.

The second initializes a types.SimpleNamespace that holds the

program’s state.

I like to wrap state up in a namespace so it is clear what is part of the

program state and what is not.

def initialize_state(s):

"""

Initialize the global state.

Arguments:

s: SimpleNamespace to store application state.

"""

s.interval = 10

s.path = ''

s.inzf, s.outzf = None, None

s.infos = None

s.currinfo = None

s.worksheets_unlocked = 0

s.workbook_unlocked = False

s.directory = None

s.remove = None

After these functions are called, the program enters the tkinter event loop.

There is also a helper function that appends status messages to the progress listbox.

def statusmsg(text):

"""Append a message to the status listbox, and make sure it is visible."""

widgets.status.insert(tk.END, text)

widgets.status.see(tk.END)

The names of the functions that make up the steps of processing an ms-excel

file all begin with step.

They are listed in sequence below.

At the end of each function sets the next step to run.

def step_open_zipfiles():

path = widgets.fn['text']

state.path = path

statusmsg(f'Opening “{path}”...')

first, last = path.rsplit('.', maxsplit=1)

if widgets.backup.get():

backupname = first + widgets.suffix.get() + '.' + last

else:

backupname = first + '-orig' + '.' + last

state.remove = backupname

shutil.move(path, backupname)

state.inzf = zipfile.ZipFile(backupname, mode="r")

state.outzf = zipfile.ZipFile(

path, mode="w", compression=zipfile.ZIP_DEFLATED, compresslevel=1

)

root.after(state.interval, step_discover_internal_files)

def step_discover_internal_files():

statusmsg(f'Reading “{state.path}”...')

state.infos = [name for name in state.inzf.infolist()]

state.currinfo = 0

statusmsg(f'“{state.path}” contains {len(state.infos)} internal files.')

root.after(state.interval, step_filter_internal_file)

def step_filter_internal_file():

current = state.infos[state.currinfo]

stat = f'Processing “{current.filename}” ({state.currinfo+1}/{len(state.infos)})...'

statusmsg(stat)

# Doing the actual work

regex = None

data = state.inzf.read(current)

if b'sheetProtect' in data:

regex = r'<sheetProtect.*?/>'

statusmsg(f'Worksheet "{current.filename}" is protected.')

elif b'workbookProtect' in data:

regex = r'<workbookProtect.*?/>'

statusmsg('The workbook is protected')

else:

state.outzf.writestr(current, data)

if regex:

text = data.decode('utf-8')

newtext = re.sub(regex, '', text)

if len(newtext) != len(text):

state.outzf.writestr(current, newtext)

state.worksheets_unlocked += 1

statusmsg(f'Removed password from "{current.filename}".')

# Next iteration or next step.

state.currinfo += 1

if state.currinfo >= len(state.infos):

statusmsg('All internal files processed.')

state.currinfo = None

root.after(state.interval, step_close_zipfiles)

else:

root.after(state.interval, step_filter_internal_file)

def step_close_zipfiles():

statusmsg(f'Writing “{state.path}”...')

state.inzf.close()

state.outzf.close()

state.inzf, state.outzf = None, None

root.after(state.interval, step_finished)

def step_finished():

if state.remove:

os.chmod(state.remove, stat.S_IWRITE)

os.remove(state.remove)

state.remove = None

else:

statusmsg('Removing temporary file')

statusmsg(f'Unlocked {state.worksheets_unlocked} worksheets.')

statusmsg('Finished!')

widgets.gobtn['state'] = 'disabled'

widgets.fn['text'] = ''

state.path = ''

The remaining functions are some widget callbacks. You can look them up in the source code if you’re interested.

Conclusion

As illustrated above, GUI programs tend to have bigger code sizes then equivalent command-line programs.

First you have to think about what input and output widgets you need and how they should be laid out. Then you have to write the mechanics of your program in such a way that it “fits” into the event-driven nature of a GUI.

Of course there are lots of situations where a GUI is a much better fit for the problem at hand. But if both approaches are possible, I will probably start with a command-line program.

For comments, please send me an e-mail.

Related articles

- Reading CalculiX mesh with Python

- Building an epub from a single ReStructuredText file

- Creating a nomogram with Python and Postscript

- Statusline program in C for i3 on FreeBSD

- Writing speed on FreeBSD 13.1-p2 amd64 with ZFS